This is the last academic year of the “Between class and nation” project and as we wrap up our research, Goran and I are starting to compare the working class communities we have been studying in Serbia and Montenegro with other locations in Yugoslavia. This asymmetric comparison is a means to determine the extent to which issues of concern to workers in the 1980s were unique to Serbia (and Montenegro) or had a broader, Yugoslav resonance.

As well as consulting sources from cities and towns like Maribor, Rijeka, Pula, Banja Luka and Skopje we also wish to include perspectives from Kosovo. As well as being home to around a tenth of Yugoslavia’s population, the autonomous province was formally part of the socialist republic of Serbia and site of a number of tumultuous events in the 1980s.

While Kosovo as a trope is a perennial trope of Serbian (and Montenegrin) historiography and political histories of the period recount Milosevic’s rise to power via Kosovo ad nauseum, very little Yugoslav social and cultural history deals with Kosovo empirically. For example in three jam-packed and diverse “Socialism on the bench” conferences in Pula (see here and here) that showcase cutting edge research on Yugoslav socialism just a single contribution on Kosovo has featured (by Pieter Troch in 2017 -“Ideology in the periphery: the Communist vanguard in (Kosovska) Mitrovica and the ideological reform programme of the Yugoslav League of Communists during the 1960s”).

In volumes examining cultural and social history of Yugoslavia, the socialist province is largely absent (though for a noteworthy exception see Isabel Ströhle’s “Of social inequalities in a socialist society: the creation of a rural underclass in Yugoslav Kosovo” in Social Inequalities and Discontent in Yugoslav Socialism)

A recent conference in Pristina on social movements in Kosovo during socialism and the 1990s was a great impetus to start thinking about how to approach Kosovo in these terms – actually existing socialism in an actually existing place.

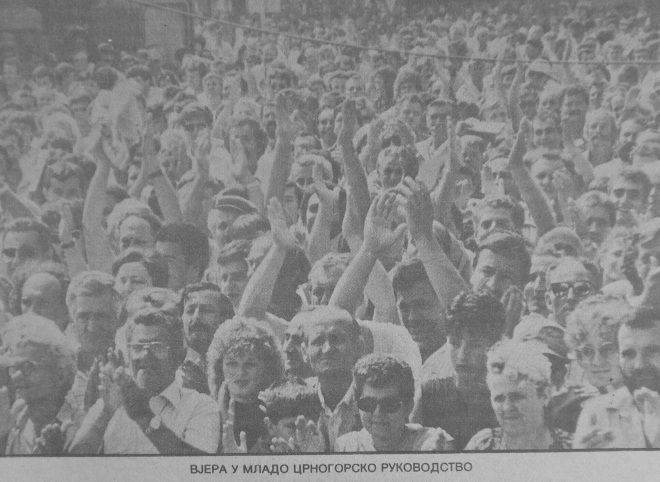

The conference, organised by Elife Krasniqi and her colleagues at Alter Habitus was a stimulating introduction to the history of social movements in Kosovo. The three day programme featured numerous activists of the 1980s and 1990s (in addition to presentations of scholars from Kosovo and beyond who switched between English and Albanian). Vetëvendosje’s Albin Kurti popped in from the election campaign trail to speak about the 20th anniversary of the 1997 student demonstrations with Mihane Salihu Bala and Bujar Dugolli (see here). Keynote speeches were delivered by feminist activists Shukrije Gashi and Igballe Rogova and was followed by a promotion of the Albanian language translation of Mary Motes’s Kosova Kosova: predlude to war 1966-1999 (which, as Konrad Clewing pointed out, is one of the rare accounts of every life and history from below in socialist Kosovo).

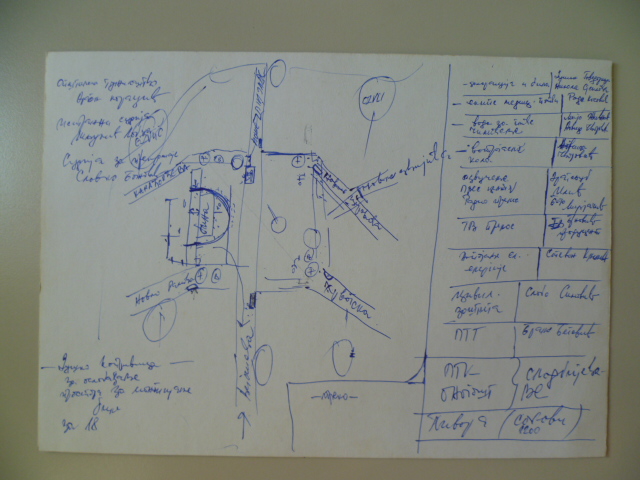

For the panel on working class and social movements we presented ongoing research which diachronically explores the ways in which workers and managers articulated problems related to Kosovo in the Belgrade working class suburb of Rakovica during the 1980s. This is an attempt to uncover (or recover) more nuanced, multi-layered perspectives of Yugoslav brotherhood and (dis)unity along the Belgrade-Pristina axis.

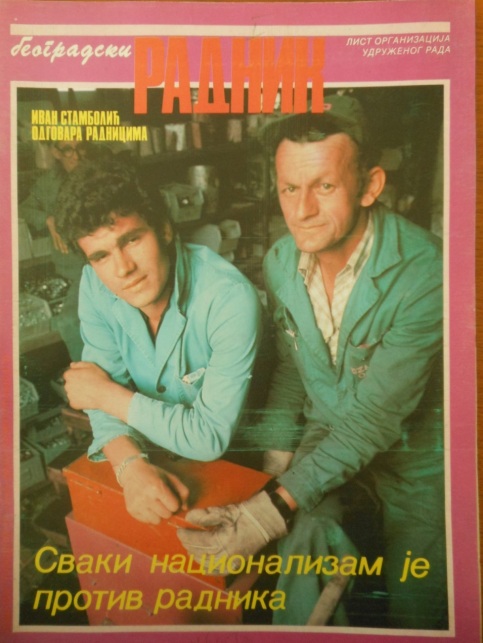

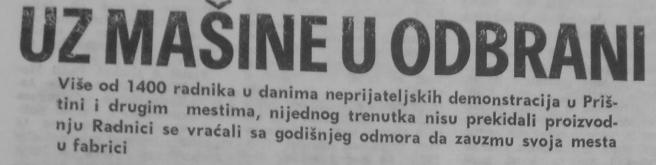

The thrust of the argument is that for many workers in Rakovica in the early 1980s (following the immediate fall-out of the 1981 demonstrations in Kosovo) the antidote to Albanian nationalism was not considered to be the greater unity of the Serbian nation, but in the insistence on the more integral (Titoist) Yugoslavism and the strengthening of class-consciousness to combat delinquencies in the system. In this way Rakovica’s workers diverged from Serbia’s nationalist intelligentsia until well into the second half of the 1980s when a reinterpretation of the hitherto dominant notion of dichotomy between the ‘exploiter and the exploited’ would be expressed in nationalist terms and any semblance of solidarity with the Albanian working class had evaporated in Rakovica.

The (yet unfinished) goal of the research is to better situate Kosovo in the historical narrative of Yugoslav labour history – beyond its symbolic value – through empirical research. But can working class communities and labour movements in Kosovo be approached in a similar way to Serbia and Montenegro in terms of the methods and sources we have been utilising?

One obvious barrier is that documents and media from the 1970s and 1980s are often in Albanian. While most Serbo-Croatian speakers can get the gist of a text in Macedonian and Slovene, this is not the case with Albanian. Beyond surmountable linguistic barriers however, is a more pressing issue – the (un)availability of sources and the particular context they were produced in.

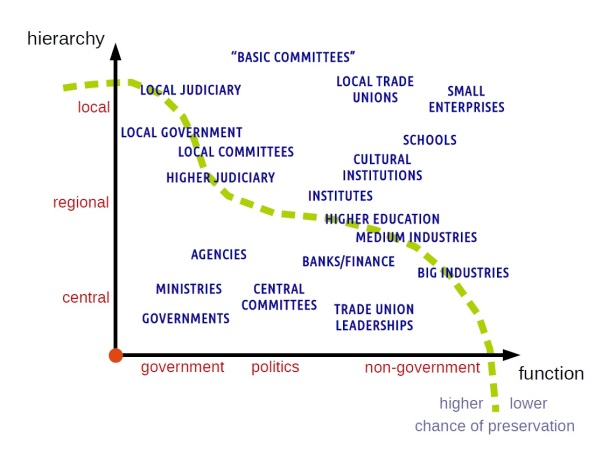

While locating and accessing factory sources in Serbia and Montenegro is not always easy, the coercive conditions in Kosovo after 1981 (and more significantly after 1989), complicate this even further. Regular and comprehensive factory periodicals are the “bread and butter” of Yugoslav labour history between 1976 and 1989. In conditions of socialist pluralism they represented sites of quite diverse viewpoints relating to the workplace and the broader social context (e.g. on housing, leisure, politics, family life). While these were certainly constrained to varying degrees in Serbia and Montenegro examples of blatant censorship are far and few between (see: Archer and Musić 2006, pp. 55-56).

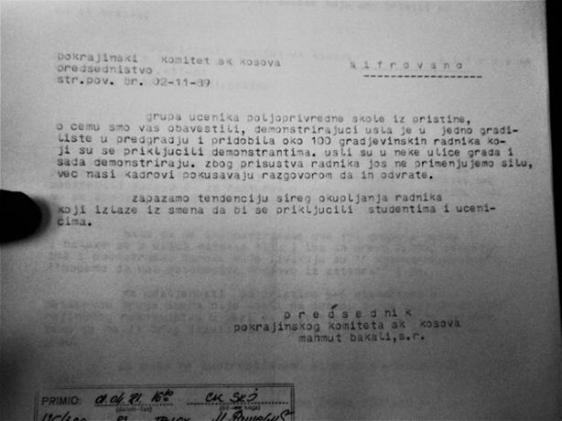

In Kosovo however, the repression following the protests of Spring 1981 resulted in some workplace periodicals simply vanishing for months at a time. For example, the large rubber plant and tire producer “Ballkan/Balkan” in Suva Reka, Kosovo, regularly published its bilingual periodical but stopped abruptly for a number of months after March 1981. Its first issue after the 1981 demonstrations featured a reprint of a text admonishing the events of Spring 1981 republished from Belgrade tabloid Politika Ekspres.

While the archives of factories in Serbia and Montenegro are not always accessible, Kosovo archives are complicated further by multiple and mutually hostile administrations (in addition holdings at Kosovo state and municipal archives some holdings were moved to Serbia in 1999, see: here). Some factory archives are reportedly in the possession of the Kosovo Agency for Privatisation.

One “creative” way to access documents may be to seek out Kosovo related material in other Yugoslav archives. For example archives in Slovenia or Serbia hold communication with and reports from the authorities in Kosovo. For a bottom-up perspective however (i.e. detailed materials at the level of the community, workplace or municipality) such documents are less insightful.

Oral history is perhaps best poised to gain insights into the world of work in late socialist Kosovo and fill in the historical record, particularly in the absence of other sources. The Kosovo Oral History Initiative is an excellent resource and platform (though the diversity of oral histories showcased does not yet extend to workers and labour movements).

Rory Archer, 11.10.2017.

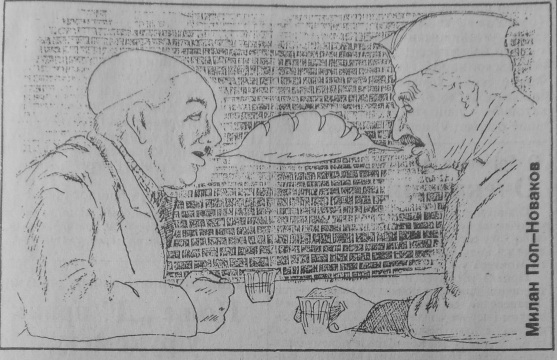

![marxovo nasljedje Marx's legacy - "It’s really not ok. He left them [managers] capital but us [workers] only the manifesto!" Jugolinija, Rijeka, broj 106, 1984, str. 44.](https://yulabour.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/marxovo-nasljedje.jpg?w=242&resize=242%2C144&h=144#038;h=144)